We can’t count the number of times we’ve heard people say that listening to music over Bluetooth A2DP doesn’t sound as good as if you played a WAV file directly from a USB memory stick. So we fired up the Sony XAV-AX7000 multimedia receiver that we reviewed in late 2020 and made a series of tests to take a look at this. The results might surprise you.

Testing Bluetooth Audio Quality

While we performed at least a dozen comparisons between the quality of direct WAV file playback and that of an audio signal streamed from a nearby computer to the radio, one test in particular stood out to provide meaningful information. We’ll look at some basics first, then show where there was a big difference.

Our test setup used a Sony XAV-AX7000 multimedia receiver with the front preamp outputs feeding into our RME Babyface digital interface. The Babyface Pro is a crucial part of the testing we do. It provides exemplary noise and distortion performance to capture audio and test signals without adding significant noise or distortion. To serve as our reference, we played our composite audio test file from a USB memory stick connected to the Sony radio, then captured the output using the Babyface. Next, we repeated the process, but this time we used a Bluetooth 4.0 USB dongle connected to our test PC and played the audio file from the computer to the radio, then captured the output, once again using the Babyface. Because many of the test signals are quite high in amplitude, we monitored the radio’s output using our oscilloscope to ensure that the signal was never clipped.

We tested both configurations for frequency response using sweeps, pink noise and white noise. We looked for the addition of unwanted ringing using impulse tones. We analyzed harmonic distortion using pure test tones and evaluated intermodulation distortion using CCIF test tracks. We’ll show you the results, including analysis of the original digital audio signal compared to that of the two recordings.

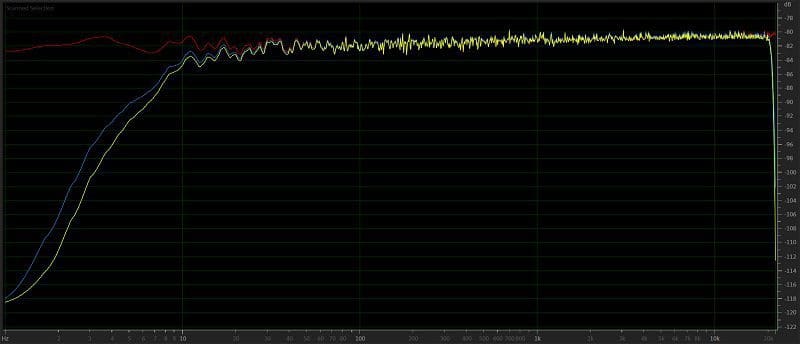

Bluetooth Frequency Response

If someone were to have asked us whether Bluetooth can handle the same audio bandwidth as an uncompressed stereo 44.1kHz sample rate, 16-bit audio file, we’d have bet money that the answer was no. So what did our tests show? It most certainly can.

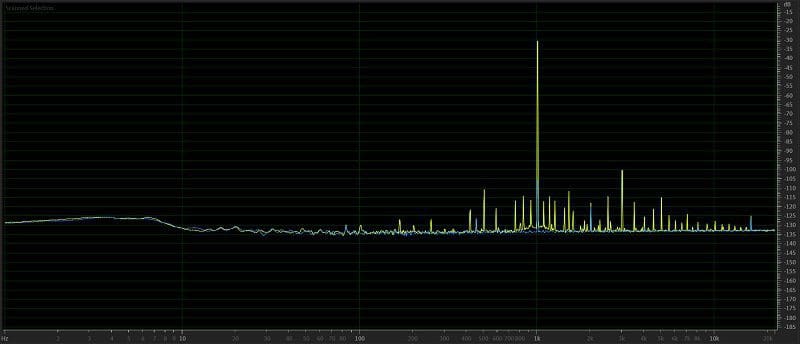

The two graphs above show the frequency response of our digital test file in red, the output of the radio playing the WAV from a USB memory stick in yellow and the output when the audio was streamed over Bluetooth in blue. The slight low-frequency attenuation below 20 Hz is common to both sources, and more importantly, both can reproduce audio up to 20 kHz without any issue. Call us both pleased and surprised.

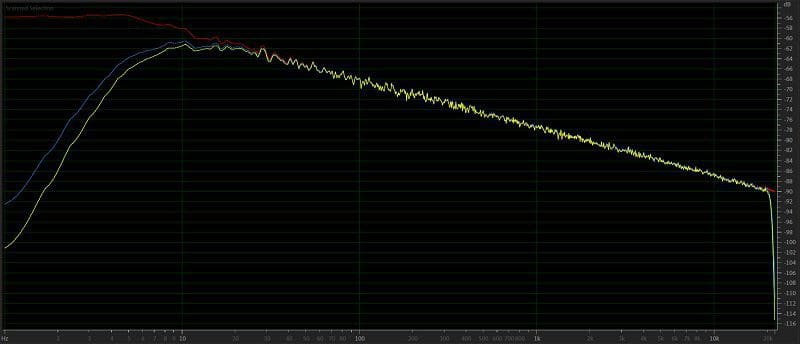

Bluetooth Crosstalk Testing

Crosstalk measures how much audio signal is leaked from one stereo channel to an adjacent channel. In these tests, the left channel contains a 1 kHz test tone, and the right has complete silence. To keep the graphs understandable, we separated each source.

We can see no leakage of the test signal from the left to the right in our test signal.

When streamed over Bluetooth, the Sony radio produced output in the right channel 86.5 dB quieter than what was played in the left. This is an outstanding performance.

When our crosstalk test signal was played from the USB memory stick, the right channel had an output that was 76 dB below the left channel. This isn’t quite as good as the Bluetooth stream but is still considered very good performance.

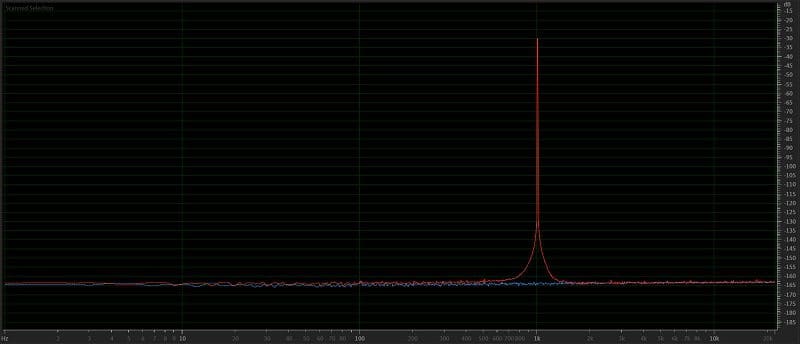

Bluetooth Harmonic Distortion Testing

Harmonics are multiples of a fundamental frequency. For example, the first harmonic of a 500 Hz test tone is 1 kHz, and the second is 1.5 kHz, the fourth is 2 kHz and so on. Harmonic distortion is the addition of information at multiples of the original signal. Because this mimics how we hear sounds in nature, such as instruments and voices, harmonic distortion isn’t all that unpleasant until the levels become significant.

To test the harmonic distortion characteristics of Bluetooth versus a WAV file, we recorded a 1 kHz test tone at -30 dB in both audio channels. The results of our testing are shown below.

The results of the distortion testing are complicated and need thorough analysis. Looking at the red trace, we see a pure 1 kHz reference tone with no other information visible. The blue trace recreates the 1 kHz tone faithfully but adds harmonic distortion at 2 kHz, 4.5 kHz and 6.5 kHz. The 2k trace is normal harmonic distortion. The 4.5 and 6.5 aren’t normal as they aren’t integer multiples of 1 kHz. You can also see a pair of peaks on either side of the 1 kHz tone at 900 Hz and 1,100 Hz. This distortion is more common when testing for intermodulation distortion and can, along with the 4.5 and 6.5k tones, sound unpleasant.

Looking at the yellow trace, we see the addition of typical harmonic information. There is information at 3 kHz and 5 kHz. While ideally we’d have no additional information, this is typical and quite acceptable.

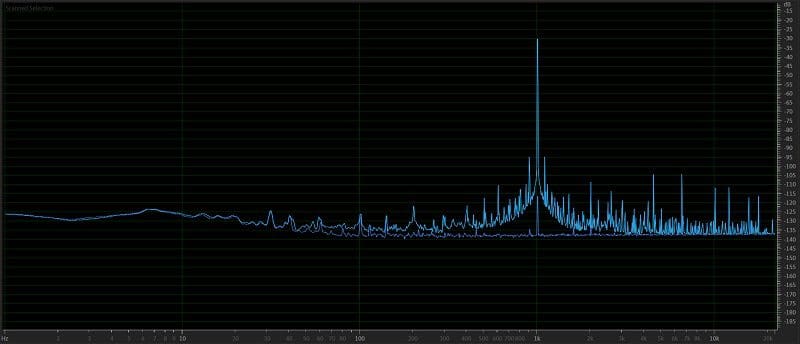

Bluetooth Intermodulation Distortion Testing

The last test we’ll look at is designed to show distortions that aren’t linear. Where harmonics are multiples of individual frequencies, intermodulation distortion can add or subtract the difference between two simultaneous frequencies.

The test we used was known as the International Telephonic Consultative Committee (CCIF) intermodulation distortion test. As this committee no longer exists, the test standard has been adopted by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) and is now known as the IMD (ITU-R) test.

This evaluation involves playing two tones simultaneously – in this case, 19 kHz and 20 kHz. The difference between 19 and 20k is 1 kHz, so poor performance would show the addition of information at 1 kHz. The test will also demonstrate how unwanted information is added at multiples of 1 kHz on either side of the 19 and 20k test signals.

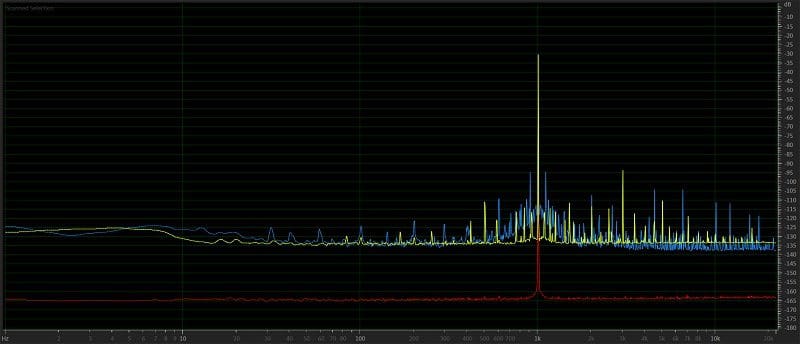

The test results aren’t absolute as they show that the different sources deliver significantly different distortion characteristics. The red trace is our test stimulus – two tones at 19 and 20 kHz, both at the same level. The yellow WAV file trace shows the typical behavior we expect to see when analyzing an audio device. There’s some signal added at 1 kHz, and more at 18 and 21 kHz. However, the levels are quite acceptable for a consumer product.

The blue trace is much more confusing to unravel. While there is some unwanted information at 1 kHz, the groups of four peaks at 2k to 3.5, 7.5 to 9k and 10 to 14k are simply abnormal. Thankfully, they are low enough in amplitude (peaking at -75 dB from the reference signals) that they don’t destroy the listening experience.

Keep in mind that audio signals contain thousands of frequencies, all played at the same time. Harmonics and intermodulation sums, differences and products are created for every single one of those frequencies. The more distortion there is, the less lifelike your listening experience will be.

Conclusions on Bluetooth Audio Quality

We would have said the measured performance of Bluetooth streaming versus the playback of a WAV file would vary more. Many variables can affect performance. Considerations for which Bluetooth codec is used depend on the phone or device you are using and its software. For this test, the Bluetooth dongle we chose uses the Qualcomm CSR8510 A10 chipset, which offers Bluetooth 4.0 +HS connectivity. The specs for the Sony radio include Bluetooth 3.0 and support for the A2DP protocol version 1.3. As always, the performance of your specific combination of car radio and audio source may vary.

Bottom line, we honestly expected a disaster, and that’s not what the testing showed. This is excellent news for folks who enjoy streaming music from their smartphone to their radio. If this sounds appealing, drop by your local specialty mobile enhancement retailer today to learn about the connectivity and Bluetooth streaming options available for your vehicle.