I’ve listened to a LOT of car stereo equipment since I started in the car audio industry back in 1988. Since 2000, I’ve tested and formally reviewed hundreds of car audio products for publications across North America. I’ve even developed subwoofers, speakers and DSP-equipped amplifiers for one of the companies I worked for. I was a car audio sound quality competition judge for more than 20 years, back when that was a popular thing. As such, I’ve developed a pretty good ear for which stereo systems and components sound good, what sounds bad, what sounds nice and what sounds right. What does “right” mean? I’ll explain.

My Introduction to Amplifier Distortion

What makes one amplifier sound different or better than another? I’ve published several articles that explain how harmonic and intermodulation distortion affect what we hear when listening to an amplifier. Likewise, I include information like frequency response measurements of amplifiers connected to complex reactive loads with the Test Drive Reviews I create. But how do these measurements correlate in terms of our perception of amplifier quality in the real world? Let me provide you with a real example of how I learned about the importance of this information.

Sometime around 2013, I talked to a friend about a brand of European-made amplifiers, and I mentioned that I’d never had a chance to audition one under controlled conditions. He had these amplifiers in his car but was upgrading to even higher-end models. So, he offered to lend me one to audition under controlled conditions in my listening room.

A week later, the amp showed up, and I connected it to my Polk Audio LSi9 bookshelf speakers and one of my modified Clarion DRZ9255 source units (I have three of them). I went through my usual test tracks that include male and female vocals to evaluate midrange purity, orchestral recordings to get a sense of the soundstage and electronic music to quantify impact and dynamics. The amp was easy to listen to. It could be described as warm and rich. I spent several hours listening to it and taking in the subtle nuances and characteristics of what I heard. My takeaway was that this amp sounded nice, but the experience didn’t wow me, as enjoyable as it was. I wasn’t sure why.

As I was finishing and began packing the amplifier up, I reminded myself that I should compare the amp to a known reference. I have an ARC Audio SE2300 two-channel, high-bias Class-AB amp in the lab that I’ve used for decades for just such a task.

The difference between the two amplifiers’ sound couldn’t have been more pronounced. The SE was incredibly dynamic by comparison. I’d go so far as to describe it as violent when the volume was cranked. Snare drum rim shots made me wince. Bass frequencies had more definition. When it came to vocals, it was as though a heavy wool blanket had been removed from in front of the speakers. Each instrument on the soundstage had better focus, and there was a larger sense of space between instruments. I was confused by the dramatic difference between the amplifiers as I had no way of explaining what I had heard. Friends, the proverbial rabbit hole had been opened.

Time to Spend Some Money

Over the next few months, I read as much as I could about amplifier testing. First, I analyzed the fantastic data that John Atkinson contributes to amplifier and source unit product reviews for Stereophile magazine. Then I tried to correlate that information with what the reviewers described. Usually, there was a direct connection, but not always. I’d attribute those disconnects to the reviewer not wanting to be overly negative about a product. Anyways, that’s a topic for another article.

Nevertheless, the next step was for me to invest in more test equipment for my lab. I bought a new digital oscilloscope, and I upgraded my multimeter to a top-of-the-line Fluke (from a mid-level Fluke) with more precision. In addition, I purchased an audio analyzer from QuantAsylum (which I’ve since upgraded to their latest version). I also bought a studio-grade digital audio interface from RME.

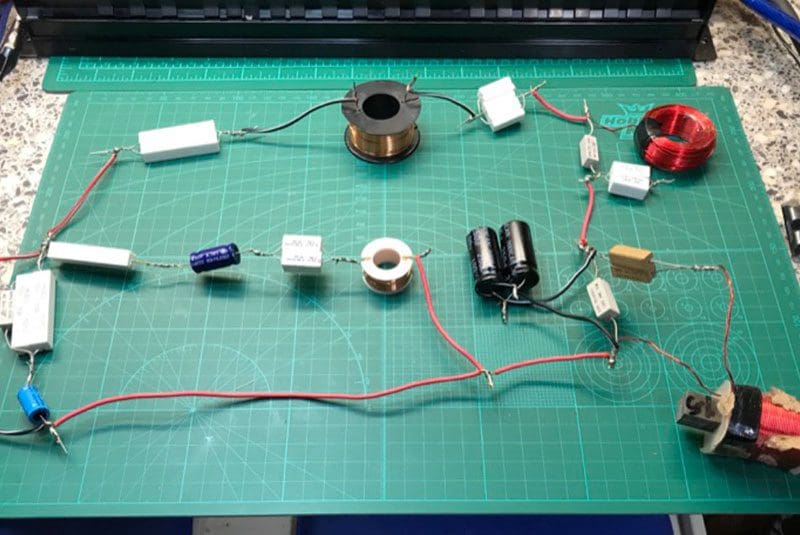

Thanks to my friend Frank at The Speaker Shop in Toronto, I recreated the reactive speaker load that Stereophile continues to use to this day. The network of capacitors, resistors and inductors simulates a small two-way bookshelf speaker. This load would be similar to a two-way component speaker set with a well-designed passive crossover network and the woofer installed in a vented cabinet in the car audio world. I’ve added a few extra resistors to the circuit to lower the overall load impedance to something more suited to car audio applications.

Last but certainly not least, I created dozens of test tracks that allow me to analyze the performance characteristics of car audio equipment. Some of the tracks are simple test tones, and some are different types of noise or noises that have been filtered at specific frequencies. Finally, some replicate industry-reference tests for things like intermodulation distortion.

After more than a week of familiarizing myself with the new gear, installing drivers and doing benchmark measurements, I started testing the amplifiers and source units in my lab. Slowly, everything started to make sense. My go-to products like the ARC Audio amplifier and Clarion DRZ9255 consistently measured better than the more affordable products I have here regarding harmonic distortion, intermodulation distortion and noise. I’ve used this data and tested many more products to create articles that are available here on BestCarAudio.com.

Speakers Add the Most Distortion

Around the time I was upgrading my test equipment, a former co-worker introduced me to a new brand of car audio speakers. The initial introduction was a white paper outlining the brand’s product development philosophy and the distortion-reducing features included in its products. I’d heard of some of these technologies, while others were new to me. I was both baffled and impressed that speakers could be this complex. Honestly, I thought a coil, magnet and a well-damped yet rigid cone were enough. Boy, was I wrong! I invested in a complete set of these speakers for my car, based purely on their technology presentation.

Just as with the amplifier testing experience, I was again baffled by the stunning improvement in clarity and detail these new drivers offered. Speakers that I’d heard and praised in the past were now merely mediocre. More research was required. In the intervening years, I’ve developed a much better understanding of how speakers work. Features like aluminum shorting rings, copper caps, flat-milled voice coil windings, flat progressive spiders and large-diameter, low-mass coils make an audible difference. Like, night and day – not subtle at all.

Top Fuel NHRA teams build race cars to do one thing to the best of their ability: cover 1,000 feet in as little time as possible. If they find better materials or technology, even something that will shave 0.001 second off of their elapsed time, they use it. Formula 1 teams operate similarly.

In the same way, speakers that implement distortion-reducing technologies sound better. They are more accurate because they add less unwanted information. It’s NOT rocket science, but it IS something that many salespeople, product developers and consumers don’t understand.

One of my all-time favorite and concerning comments about an audio product was made by Robert Schryer in his review of a set of French-made home audio speakers. He said, “The (speakers) endowed the music with a warm, hearty tone that sounded as unclinical as I could imagine music sounding.” Wait, shouldn’t what you hear sound precisely like the original recording? Clinical sounds like a compliment to me.

When It Comes to Audio Systems, There’s Bad, Nice and Right

I’m not an audio snob. If I rent an inexpensive car on a trip, I turn on the radio and enjoy listening to music. Sure, I’ll observe how accurately it reproduces different frequencies and how it places the music in the vehicle. But even if it’s terrible, I don’t turn it off. Music is an escape. It’s fun to hear how talented musicians express themselves and share a story.

When it comes to being picky about the products I use and recommend, it boils down to this: Some products don’t simply don’t recreate music accurately. They add distortion that no amount of signal processing can remove. Distortion is any unwanted information that wasn’t in the original recording. It might be perceived as “warmth” or an unwanted emphasis or dip in a specific frequency range. Yes, you can equalize the output flat, but harmonic content can’t be removed.

Distortion might also be time-based. An excellent example of this is a high-Q woofer that resonates or rings after the signal stops. This distortion will add emphasis to the midbass and lower midrange region. Distortion might also come across as softness to the sound. Does a rim shot on a snare drum have a snap that scares you, or does the drum stick sound more like it’s made of rubber? Vacuum tube amplifiers are notorious for this “softness.” In fact, bass frequencies from the stereo in my 2015 Hyundai Genesis sedan would best be described as slow and sloppy. There’s no snap, no thud, no bang. At best, I get a bump or boof.

Great audio systems can provide a sense of the size of the room where the music was recorded. They make voices sound authentic. Whether you listen to Holly Cole, Lorde or Billie Eilish, it should sound like a woman singing to you, not like a recording played back through a boombox or worse, a clock radio. I was recently in a 2021 Hyundai Venue compact SUV. The audio system was so bad that my iPhone’s Siri voice prompts sounded terrible. That was the worst car audio system I’d heard in a very long time.

A piano is an instrument many of us have heard at school, in church or at a club. But does your car stereo reproduce a piano recording as if the instrument were in the car or truck with you? Can you hear the vibration of each string down to an A0 at 27.5 hertz? Does the volume remain constant as the performer moves up and down the keyboard? High-end audio systems are supposed to sound real, not just be expensive. Yes, you might want a little more bass to make the lowest frequencies audible when on the highway, but the instruments and performance should still be accurate and realistic.

What about the relationship between the cost of car audio products and their performance level? Do I think everyone has to spend $10,000+ on equipment to upgrade their audio system? Absolutely not! We all have different budgets and performance expectations. This is where value comes into the conversation. There are excellent speakers, subwoofers and amplifiers that only cost a few hundred dollars. This challenge here is to find products that perform well at a price point that works with your budget and commitment to accuracy and realism. These products might not offer the same performance as a flagship model, but if they sound better than everything else at their price, then they are a great choice. Finding these solutions can take some work, and more importantly, a dedication to auditioning products properly before purchasing them.

The world of high-end home audio speakers is rife with options that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars yet don’t sound as accurate as some speakers that cost around $22,000 a pair like the JBL units I mentioned earlier. I guess there are no bragging rights among the super-rich if you didn’t spend a quarter-million dollars or more on your stereo system — such nonsense. Headphones are even worse. I see sets costing $3,000 to $5,000 that don’t sound as clear and detailed as some that are only $550. The same holds true for some car audio systems. I’ve auditioned many products with high price tags that ship in a fancy flight case and are blessed with nonsense marketing stories yet sound mediocre. They have a “sound” or balance that isn’t how the music sounded at the console in the recording studio. We aren’t talking about more bass or highs. Everything is different. They don’t sound right.